As a fan of Alabama football, I find few things more exhilarating than attending a game in Bryant-Denny Stadium. To be on hand for a key contest with 101,820 of my fellow Crimson Tide fans is an experience that can scarcely be put into words. The wins are electrifyingly ecstatic and the losses are devastatingly brutal. Never is it boring.

This experience is repeated to a greater or lesser degree for anyone who attends a sporting event where they are emotionally invested in the outcome. There is a tribal sense of purpose and a bonding in the shared experience that we cannot quite express to others afterward. "You had to be there" is less a cliche than a testament to the insufficiency of language in certain instances.

Yet for all this you remain a spectator at a performance. The athletic contest unfolds before you but almost completely beyond your ability to affect in any way (except for your lucky shirt, of course). In this respect, marathons are the exact opposite. Last November more than 46,500 people finished the ING New York Marathon. The spectators, in this case, were the participants.

Part of the appeal of the marathon (and other endurance events) is in being the athlete in competition rather than witnessing to the action. In this respect it is rather unique in the pantheon of modern sports; far more people participate in marathons than those who follow it simply as fans.

To get an understanding of how vastly different the experience between endurance racing and other major spectators sports it's helpful to compare the evolution of marathon running as a sport versus football.

Once upon a time, football’s main way of cashing in on its popularity was the gate. The result was a boom in stadium construction in the 1920s as football’s popularity began to expand beyond its regional origins. It isn’t by accident that this time period saw the emergence of professional football and the forerunner of today’s NFL – the American Professional Football Association.

In the 1960s this equation began to change due to the emergence of television. It became possible to witness the contests themselves without being in attendance and the popularity of football simply skyrocketed. At first rigid protections were put in place to protect the windfall of the gate but fears of declining attendance turned out to be unfounded.

Football became bigger than ever as televised broadcasts dramatically widened the audience. Yet, ironically, the proportion of the games players to the number of spectators was reduced to an almost infinitesimal degree. That’s a stark contrast to marathoning which saw the exact process evolve in reverse.

While football was emerging as a popular sport in the first half of the 20th century, marathons and other such distance races were purely an oddity. There were a handful of annual events and, on occasion, a well publicized endurance event but interest was confined to a core group of enthusiasts. What interest there was tended to be confined to track and field and, by extension, the Olympic Games.

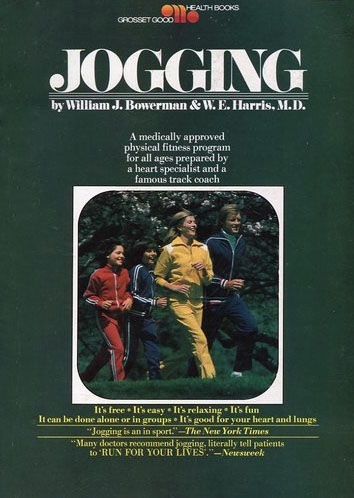

All that changed in the 1970s with the jogging phenomenon. The concept of running as an organized public activity began in New Zealand but was exported to the United States by the University of Oregon’s famed track coach Bill Bowerman. His book "Jogging" became a best seller and the clubs he championed quickly sprout up across the country. Suddenly, running had become the participatory sport of the masses.

Then, when an American, Frank Shorter, won the gold medal for the marathon in the 1972 Summer Olympics, the boom was on. Existing races saw their participation numbers increase and a whole slew of new marathons appeared and, increasingly, people were showing up to run in them.

Television, notably ABC’s Wide World of Sports, would broadcast certain marathons but the sheer inability to sufficiently transmit the drama of the event through the medium limited its appeal. The endurance required to run a marathon – even at the most competitive level – is too much to ask of the general viewer. And the length of the event barred any type of cohesiveness in the experience of the spectators.

This whole interesting relationship is summed up for me as a running in terms of the country’s flagship race, The Boston Marathon. The Patriots’ Day race is the only annual marathon in the United States that you must qualify to participate. The others restrict the field via first-come-first-served or by lottery (although NYC does include priority registration for qualifying runners).

So unlike every other major sporting endeavor, it is the only one we as relatively average physical specimens can aspire to participate in ourselves.

I played football in high school and was epically awful at it. I ran track as well. While I didn’t set the world on fire as a distance runner, I didn’t completely suck either. As I got older I kept going back to running as a physical pursuit but, even with my love of college football, I never really even considered picking up a pigskin for anything more than a backyard game of catch.

The chance I would ever experience a game from the field of Bryant-Denny Stadium was pretty much zero from the beginning but the chance of running from Hopkinton to Copley Square one April is within the realm of possibility. Remote but a realistic possibility.

So when I'm at Bryant-Denny Stadium on gameday my hopes and aspirations are focused on the team on the field wearing the crimson jerseys. I am joined in glorious anxiety with more than 100,000 other fellow Alabama fans and the experience of the game is exponentially heightened as a result.

But when I'm running a marathon (or any race, really) all of my aspirations are bound up within myself. And I'm sharing that experience with the hundreds or even thousands of others participating in the event along with me. That's provides a pretty hefty emotional push but when I cross that finish line, the achievement is something that is mine alone.