Bruce Cleland remembers the date -- March 21, 1986, a Friday -- when he learned his daughter, Georgia, had been diagnosed with leukemia. She was two years old, "a happy little girl" according to Bruce, but she had been unhappy for the last few weeks. His wife Isobel, "Izzy," kept taking Georgia for repeated visits to the pediatrician, worried that her baby's on-off illness was more than teething pains.

"At one point I said ‘Izzy, just let her be, she's two years old, she's not feeling well,'" Bruce recalls. "‘Stop pestering the pediatrician, you're going to drive him crazy.'"

Izzy's intuition was correct. She called Bruce at his office that day to tell him that their daughter had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, also known as ALL. "It was the worst thing I can ever remember happening," according to Bruce. He raced out of his Manhattan office and took the train back home to Rye, N.Y. That moment of panic set in motion the events that would lead to the formation of Team In Training, and the start of an enduring connection between charity and endurance sports.

***

Within a few days, the Clelands were referred to a leukemia specialist. The doctor suggested getting in touch with the local Leukemia Society of America office -- now the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society -- where they found day-to-day support, as well as access to research and public education. Within the year, they became heavily involved in fundraising, which meant attending events and imploring friends to donate.

"People are very generous, particularly when you have a life threatening illness to a young child," Bruce says, but generosity hit its limit at some point. After a few months, the Clelands began running short of donors.

"One guy even said to me ‘you know it's really expensive being your friend.'

"You ask them once and they're more than happy to help, the second time they help again," Bruce says. "The third time and maybe even the fourth time they begin to look at you sideways, you know?"

The idea to run a marathon first entered Bruce's mind in January of 1987. Not as a fundraiser, mind you, but because Bruce had fallen out of shape. He was born and lived in New Zealand until he was 23, and grew up a devout rugby player under the shadow of the famed All Blacks. He played in London after leaving the southern hemisphere, and played at the New York Athletic Club when he came stateside.

That is, until nagging knee problems set in. Bruce was getting a bit older and a bit slower, too. "Once they can catch you it's not much fun anymore, because then they drill you."

The natural progression of life also caught up to Bruce. He got married and had kids, and was traveling around the world for work. Bruce says that he was roughly 33 years old when he hung up his rugby cleats, and hadn't truly maintained his athleticism for more than a decade when he began to consider running. A marathon still seemed daunting.

"I just couldn't see how I could ever do it. It wasn't a common thing in those days," Bruce says. "The people who ran marathons way back then were strange skinny people."

Bruce changed his mind while reading the New York Post on his way home from work in November, 1987. The Post ran a picture of a man named Bob Wieland as he crossed the finish line at the New York City Marathon. Wieland clocked in at 81 hours, more than three days after the fastest runners had finished the race. No calamity befell him during the race, and, in fact, his time was nearly 18 hours faster than the time he posted the year before.

Wieland took so long to run the marathon because he "ran" the Marathon in the loosest sense of the word. Having lost both of his legs to a buried mortar during the Vietnam War, Wieland sat his torso on a skateboard, donned a pair of heavy duty gloves and propelled himself to the finish on his fists.

Bruce was galvanized.

"It sent shivers down my spine, and here I was complaining about being overweight, and a sore knee from old rugby wounds, and this guy with no legs had just finished a marathon in three days," Bruce says. "It was a very humbling thought."

Several forces converged at that moment. Bruce wanted to shape up, but he was also dedicated to his daughter and blood cancer research. He also knew he didn't want to undertake training alone. The idea hit him: Put together a group of like-minded individuals, train together and solicit sponsors. The group would aim to be ready for the 1988 New York City Marathon. Team In Training began from that moment forward.

***

The first Team In Training. New York, 1988.

The logistics were exhausting. Bruce decided that the team could consist of at most 40 members before becoming unwieldy. Of course, in the 80's, getting 40 people to show up at the same place at the same time meant going through the cumbersome process of placing 40 phones calls to land lines.

Finding runners for the team was also a chore. Many people thought as Bruce once had, that marathons were strictly the domain of "strange skinny people." Bruce made them a deal.

"Originally I was trying to recruit people for the team and they said ‘no way,'" Bruce recalls. "So I said ‘if you're not going to join the team, the least you could do is sponsor me.'"

Many of those early sponsorships took the form of wagers. Several sponsors even wrote "only to be paid if you finish" on donation forms.

Despite skepticism, Team In Training gained traction. Bruce found runners, tasking each member to solicit $5,000 in corporate donations with hopes that even if a few members fell short, the team could raise as much as $150,000 as a group. Once he had enough interested runners, Bruce then had to make sure he could get entries. Applications could not be sent until a particular date, so several members camped outside a New York city post office overnight to make sure the Team In Training applications were the first to be postmarked after midnight.

As Bruce worked tirelessly to find corporate sponsors, he also scrounged up celebrity support. New York Mets Hall of Fame catcher Gary Carter and New York Giants defensive end Leonard Marshall both lent their likenesses to the cause as two of three honorary sports chairmen. The third chairman, Rod Dixon, was a bronze medalist in the 1500m for New Zealand at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games and the winner of the 1983 New York City Marathon. He proved to be pivotal to Bruce's efforts.

***

Bruce had met Rod earlier through a mutual friend. Rod was in New York to meet with his sponsors at Pepsi-Cola, which happened to be headquartered in Rye where Bruce lived. So Rod gave Bruce a call, and the two men met face-to-face for the first time at Bruce's front door. Rod had a wife and two young children in tow, and the two men formed a fast friendship. Rod and his family lived with the Clelands for three months from that day on.

Bruce asked Rod to help coach the team, and Rod accepted. In addition to training advice, Rod also brought in other accomplished runners to speak at meetings and lend their own guidance. With a world class runner on board, the team grew closer and sponsors were more apt to give. "It gave what we were doing a lot of legitimacy," says Bruce.

After 10 months of training and meticulous planning, all Bruce and his team had left to do was run. No problem. All 38 members of Team In Training completed the New York City Marathon on Nov. 6, 1988. At 41 years old, Bruce clocked in at five hours, 23 minutes. More importantly, the group raised $320,000 for the LLS, more than double the goal Bruce set at the outset.

"It was a magical experience in that the way we conceived it at the outset, it actually came off," Bruce says. "Those of us who were overweight to begin with lost heaps and heaps of weight. We gained back 15 years of our youth, we really enjoyed each other's company, being members of a real team ... and most importantly we raised a lot of money for leukemia research."

Several other LLS chapters took notice of what Bruce did and started similar programs. Eventually the national office noticed too, and sat down with Bruce to work out a "playbook" that was sent out to every chapter in the United States.

Team In Training has since become the signature program of the LLS, using the same name and logo that the original team used in 1988. Celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, Team In Training has raised more than $1.3 billion for blood cancer research, and has had more than 600,000 participants complete events, from half and full marathons, to 100-mile bike rides to triathlons.

In that 25-year timespan, blood cancer treatment has improved immensely. Bruce's daughter had a 50 percent chance of survival when she was diagnosed. Today, the survival rate for two-year-olds diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia is above 90 percent. In 1960, the survival rate for all forms of leukemia stood at 14 percent, and has climbed to 58 percent since. The survival rates for those with Hodgkins and non-Hodgkin lymphoma are now 87 percent and 71 percent, respectively, up from 40 and 31 percent in the early 60's.

***

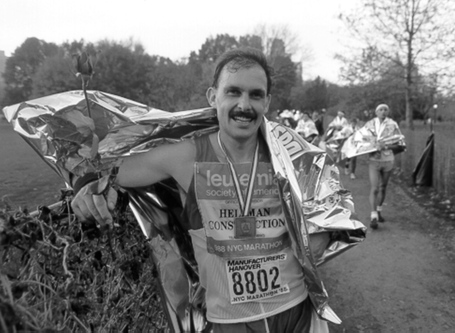

Bruce Cleland with a post-race rose. Nov. 6, 1988.

It took Bruce some time before he realized the impact his idea was having. After the marathon, Bruce stepped back from Team In Training. He stayed involved with leukemia fundraising, but training and organizing had left him fried. Bruce had three kids at home, after all, one of whom was very ill, and was trying to get a new business off the ground. He didn't have time to start a new cycle of planning, training and fundraising.

"I often said, throughout that year and probably the first two years, there wasn't a sentence spoken in our house that didn't have ‘leukemia' or ‘Team In Training' in it," Bruce says. "It was just 24/7."

Nearly a decade later, Bruce was living in Baltimore, working a new job. A girl who worked in his office approached him with a brochure and asked if he would sponsor her for an event for charity. Busy, Bruce said he would take a look when he had time. An hour later, as he was packing up his desk for the day, Bruce finally took a look at the brochure and recognized the familiar Team In Training name and logo. The Washington D.C. chapter was putting together a team for an inline skating event in Georgia. The girl had no idea that Bruce had founded the program.

"The next morning I went up to her desk and said ‘this inline skating, it looks pretty cool, how much do you know about it?'," Bruce recalls. "I said, ‘I tell you what, I'll sponsor you but only if you let me do it with you.' She said, ‘Are you a skater?' I said, ‘No, but I'm going to become one.'"

Bruce began training again. His knees were still wonky, but he figured that skating would be less stressful on his joints than running. Bruce did the event--known as Athens to Atlanta, or A2A--from 1997 to 2004. In preparation, he trained for two hours every morning before work, and went out for 3-5 hour skates on weekends.

In that time, Bruce also rekindled his involvement with Team In Training. Today, he remains deeply involved with the program, speaking at functions and consulting when asked.

Chris Fenton has spoken with Bruce several times since taking over as vice president of Team In Training in 2012. The two have talked about the future of the program, and how Team In Training can move on from the direct mail campaign strategies of the past and take advantage of the reach of social media.

But while the means of fundraising are changing, both men agree that the core tenets of the program remain the same. Team In Training will remain focused on building camaraderie through training, Chris says, and will continue to emphasize long, arduous events. The program does not want to become too heavily involved in the 5k/10k circuit.

"We want Team In Training to mean something when you see our logo. We're trying not to dilute it with a myriad of events that are maybe shorter distances," Chris says. "We have a legacy of exciting people for fundraising and having our typical participant go from the couch to the finish line of a hundred-mile bike ride or a marathon."

Longer events also mean more time spent in close proximity with teammates. Bruce echoes Chris' sentiments, saying he started Team In Training in part to harken back to his rugby days, playing a sport he says emphasizes teamwork "maybe more than any other sport I can think of."

"I've always loved being in a team-based culture, and I missed it desperately," Bruce says. "That feeling of being a part of team--supporting each other, winning together, losing together--that was a very important part of the philosophical underpinnings. The idea of being on a team and being able to achieve so much more together than as individuals."

***

Bruce Cleland and his daughter, Georgia, today.

Bruce eventually did run again. He completed the Rock ‘n' Roll Marathon in San Diego seven years ago, and afterwards said felt as if he was in the best shape of his life, "never felt better." His daughter Georgia? She was 22 years old and cancer free. Then he met with doctors.

They told Bruce he had throat cancer. Stage IV. "I had a tough time of that," he says.

Bruce underwent heavy-duty radiation and chemotherapy, but the cancer kept coming back. After the third time, Bruce went under the knife. Surgeons cut through his face, opened his throat, and scraped out the cancer at the base of his tongue. They replaced the removed tissue with tissue from his arm, and after relearning how to talk he can joke today that he is "talking to you with my wrist."

The 17-and-a-half hour procedure saved Bruce's life.

Two years later and cancer free, Bruce wanted to prove he was strong once again. More than 20 years after seeing Bob Wieland's picture in the New York Post, Bruce, at 61 years old, completed the 2008 Baltimore Marathon in six hours and three minutes.